John Crawford continues his exploration of the John Miller Fife Manuscript

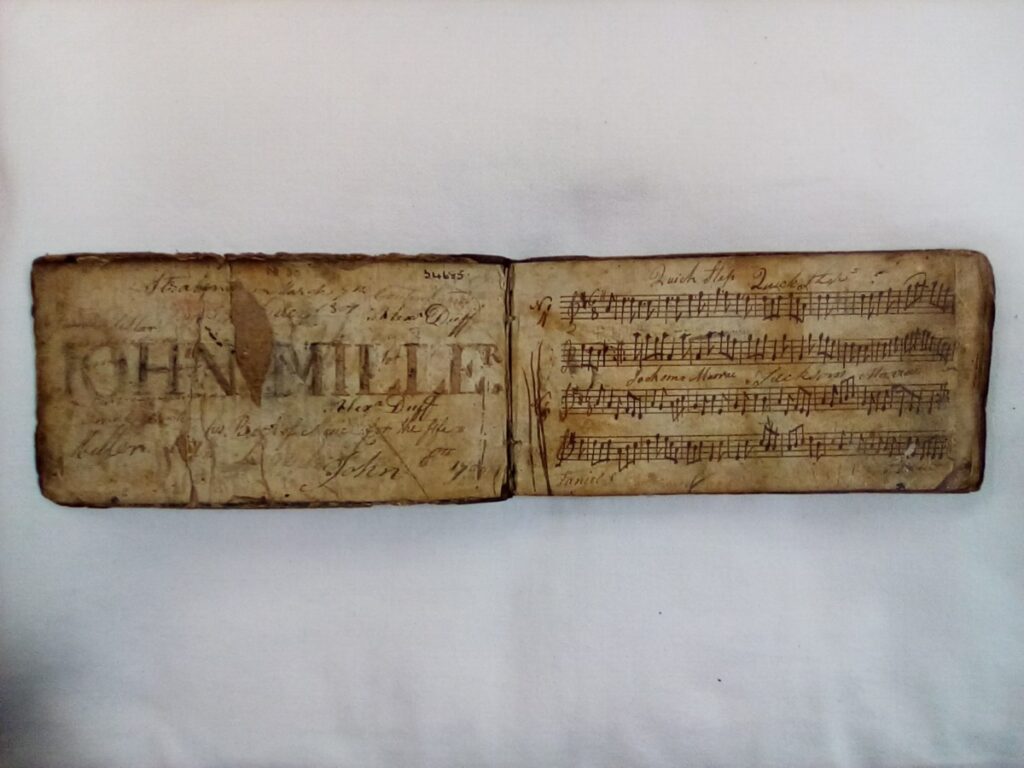

About the author: John Crawford is a long-standing supporter and co-organiser with FluteFling. John enjoys exploring the forgotten pre-revival Scottish flute manuscripts that reside in online libraries and collections, such as this Scottish fife player’s manuscript from 1799 held in the A K Bell Library in Perth. The manuscript is part of the Atholl Collection, a key archive source for the Scottish flute world.

About the author: John Crawford is a long-standing supporter and co-organiser with FluteFling. John enjoys exploring the forgotten pre-revival Scottish flute manuscripts that reside in online libraries and collections, such as this Scottish fife player’s manuscript from 1799 held in the A K Bell Library in Perth. The manuscript is part of the Atholl Collection, a key archive source for the Scottish flute world.

Part 1 of this article dealt with my early lockdown experience, pursuing the John Miller Fife MS (manuscript) I found in the Village Music Project (VMP) website. This revealed a lot about the music John Miller must have played on his fife and provided a partial understanding of the context of the manuscript, but largely left Miller and his life shrouded in mystery.

The trail to the original document pointed to the Atholl Collection and the AK Bell Library in Perth. The collection was compiled by Lady Dorothea Murray, later Ruggles-Brice, and a daughter of the 7th duke of Atholl. When she died she left instructions for it to be bequeathed to the Sandeman Library in Perth. When this closed the Collection moved to the AK Bell Library.

The general significance of the Collection has been outlined in part 1 of this Blog. The catalogue, compiled by Dr Sheila Douglas, confirms the Atholl Collection has been recognised for many years by the world’s academics, with enquiries from institutions as diverse as Harvard, the Joseph Hayden Institute in Cologne and the University of Sydney. It remains an open question whether Scottish traditional musicians have invested an appropriate level of interest in understanding the value of the collection and what it can offer them.

From a flute perspective it’s worth re-emphasising its significance in the Collection. The Miller MS is one of 60 items where the catalogue description specifically mentions flutes or fifes. This is a powerful demonstration of the popularity of fifes and flutes in the 18th and early 19th century and makes a strong case for further study of the collection. Items of note and interest include:

- Fifty Favourite Scotch Airs; for a violin, German flute and violoncello, with a thorough bass for the harpsichord – PEACOCK, Francis, Aberdeen s.n. 1782 [Ref No Bf55 26796]

- Complete Repository of Old and New Scotch Strathspey Reels and Jigs adapted for the German flute – HAMILTON John, Edinburgh s.n. 1802 [Ref No Bd49 26661]

At the time of writing the Miller MS, along with the rest of the collection, has not been digitised, making a visit to Perth essential. When Part 1 of this blog was written COVID restrictions made it impossible to see the MS at first hand and examine it in more detail.

Waiting another six months to see the MS was a challenge and a time to remember one of my mother’s favourite Gaelic proverbs about patience:

“Am fear a bhios fad aig an aiseag gheabh e thairis uair-eigin.”

[He that waits long at the ferry will get over some time.]

On Friday 10 September 2021 I finally made it to A K Bell Library to see the MS. Was it worth the wait? The answer is an unambiguous and absolute yes. I enjoyed my day immensely. Being able to see, and touch, the MS was a very powerful experience. I felt very privileged and had a very strong sense of being in direct touch with history. Probably the nearest parallels are:

- discovering an important artefact during an archaeological dig and

- that sense of connectedness you get from playing a vintage flute.

The experience was amplified by:

- the fact that what I had in my hands was a MS rather than a printed document;

- the obvious age and fragility of the document (particularly the cover boards);

- evident fingerprints, particularly on the fore edge of each leaf and

- the additional notes on some of the pages in a hand other than that of the person who wrote the tune titles.

Seeing the MS sparked some additional ideas about how the MS originally came into being and what might have happened to it, between John Miller’s time, and it becoming part of the Atholl collection. The handwriting of the tune titles is very precise and stylised; certainly the hand of a highly literate well educated individual. There’s evidence of a second less literate, less well developed hand, in pencil, in additional notation in the book.

I’m now wondering if it’s possible Miller got the book from his Bandmaster and that the second, less literate hand writing is his. Given the lack of history of the MS and how it came into Lady Dorothea’s hands it is, of course, equally possible the other handwriting is that of an interim owner.

My conversation with the library staff during the visit flagged up the material on the adjacent shelves relating to the Black Watch. The Village Music Project narrative relating to the MS, speculates that Miller might have been associated with the Black Watch or its antecedents (the 73rd (Perthshire) Regiment of Foot, or the 42nd Regiment of Foot).

My initial online research had failed to find any indication that the Black Watch, or its antecedents, was in Ireland, at any of the locations mentioned in the Miller MS (Strabane, Stranorlar and Londonderry) between 1798 and 1801. This finding appears to be supported by the additional material I found in the Library.

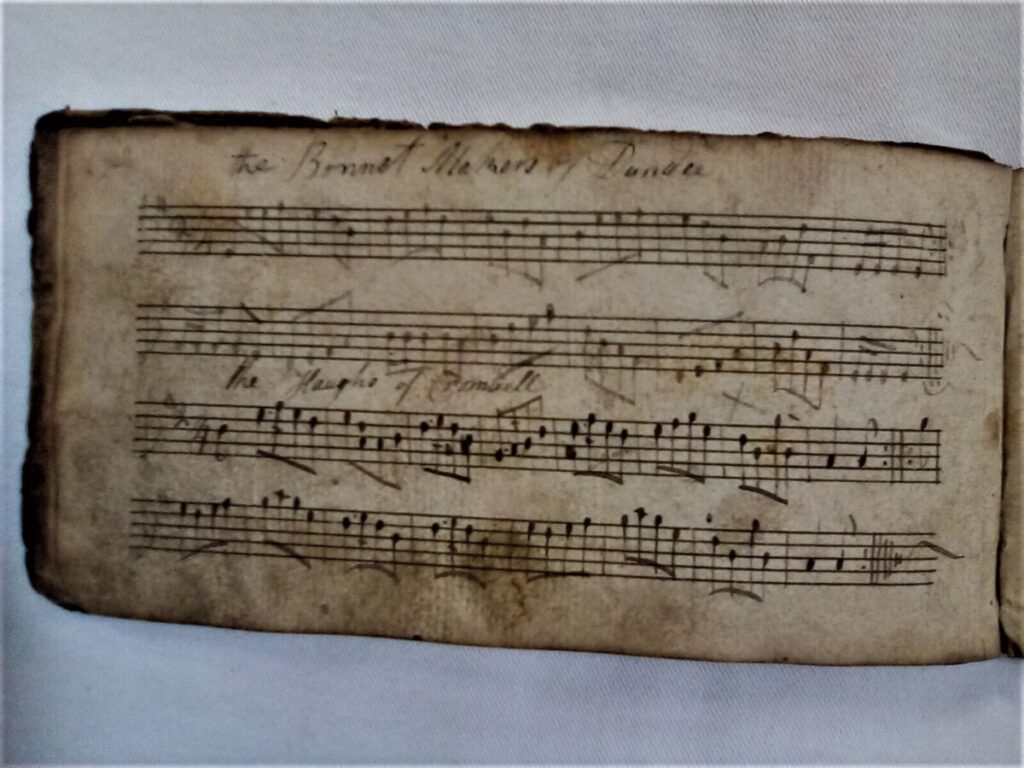

The John Miller manuscript with the tunes Bonnet Makers of Dundee and the Haughs of Cromdale (c) John Crawford.

My view, based on the information currently available, is that it’s much more likely Miller was part of the many Fencible regiments formed and posted to Ireland in the wake of the 1798 uprising and the French invasion. Unfortunately attempts so far to uncover historical sources providing detailed information on recruitment by these Fencible regiments, their bands and musicians appears to be very limited.

Perhaps this is unsurprising given the limited time these regiments existed for. The earliest regiments were raised in 1759. When it became clear that the rebellion in Ireland had been defeated and that there would be peace between France and Britain in 1802 (The preliminaries of peace were signed in London on the 1st of October 1801) the Fencible regiments were disbanded.

We may have to accept that John Miller’s history is lost to us and that we can only speculate about his age and circumstances; how he came to be recruited; what regiment he was part of and how his MS came to be part of Lady Dorothea’s collection. The repertoire in the MS suggests a Scottish connection but this is not 100% conclusive. The Buttrey Manuscript mentioned in my previous post includes a wealth of Scottish tunes. John Buttrey joined the 34th Regiment in Lincolnshire, England in 1797 as a drummer at the age of 13. He served in Africa and India and was discharged when he returned to England in 1814.

John Miller’s MS is, nevertheless, an invaluable and rather unique window offering a more human perspective on the importance of the fife in the life and music of Scottish Regiments in the 18th & 19th century than formal sources like Thompson’s 1765 Compleat Tutor for the Fife with all its duty calls. These are tunes that deserve to be played; when you do, tip your hat and say thanks to John Miller.

Scots Guards band in the Park in 1880 by Édouard Detaille. Note four ranks of fife players vs one rank of pipers. © Public Domain

Article (c) John Crawford 2022