With events cancelled and many of us in lockdown, a look ahead to what this means for FluteFling.

It’s a sunny Wednesday in Edinburgh, the windows are open and birds are busy outside. Spring is upon us and all would seem well if it wasn’t for the fact that we are in the middle of a pandemic and most people are in some form of lockdown or restricted movement. It is an uncertain and worrying time for everyone, with various concerns for health, loved ones, neighbours and colleagues, physical and mental well-being, work and finances.

It has been heartening to witness many examples of people supporting each other in the community, both locally and across the world. And there has also been much celebrating and sharing of music and song to help unite people and raise spirits in these strange and difficult times.

Traditional music connects people, places and histories and celebrates what is common to us all and the festival season would be fast approaching, when musicians, dancers and lovers of music reunite, share tunes, stories and good times together.

Traditional flute workshop with Sharon Creasey at FluteFling Edinburgh Weekend 2018 (c) Gordon Turnbull

We would have seen some of that last weekend too, with what was promising to be an amazing FluteFling Edinburgh Weekend, our seventh no less. In previous years, people have travelled far for the events in Edinburgh and Aberdeen to meet, play and learn more about traditional flute playing in Scotland and to be part of a revival. As an organiser and sometimes tutor, it is both humbling and inspiring to be part of this and to witness it take on a life of its own, fuelled by the energy, enthusiasm and support of the community that has grown up around FluteFling.

It is a particularly difficult time for those freelance musicians and performers who rely on performances and audiences for an income. Please do what you can to support them — if you buy their music, follow them on social media, share their work or reach out to them, it all helps. And look out for performances from home via various streaming apps. Facebook seems to be popular for this, but there will be other outlets too, such as Youtube.

For some of us in lockdown and not key workers on the front line, events force us to slow down, restrict our movements and reflect. For me, this slower pace and gifted time has allowed me to get the flute out more, to begin thinking about ideas for future FluteFling activities, to begin tweaking and tidying up the website. The various people who are involved in running FluteFling events will also be exploring ideas together.

On a personal note, I have found it difficult in recent months, maybe years if truth be told, to focus on some parts of my own music-making. It is true I am sure for many of us with busy lives and commitments and so maybe this is an opportunity for us all to reconnect with our own music, be in less of a hurry to learn that tune for this session, to maybe explore existing repertoire. Time to to reexamine tone and tuning, revisit ornaments and articulation, to slow down and rediscover the joys and consider what our music means to us.

I have begun to take inspiration from something Paul McGrattan shared at Cruinniú na bhFliúit -The Flute Meeting in Ballyvourney a couple of years ago. Alongside many other ideas, he suggested recording yourself once a week to monitor progress and focus your practice. So my underused YouTube channel is now going to have a new tune or set of tunes posted every Friday during the lockdown period.

To begin with at least, this will focus on tunes that I have taught or might otherwise already be found in the Resources section or on my Soundcloud account, where they are slowed down for playing. I expect other tunes, recalled, revived, relearned or newly discovered for me, will also feature on that YouTube channel.

There will be some other posts on this website, certainly more regularly than in recent months. But in the meantime, thank you everyone, for being involved, for playing and sharing your music and for being part of the traditional flute and whistle community in Scotland.

Stay safe and stay well and we will see each other on the other side when this is all over. The next FluteFling Weekend, whenever that may happen, will be quite some celebration, for sure.

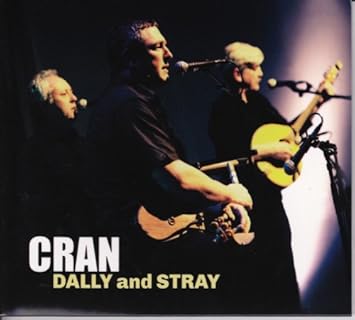

Hunt the Squirrel has a rich history. The Sleeve notes for Cran’s Dally and Stray CD seem to be no longer available online, but a search around sees it associated with Dumfriesshire and Ayrshire.

Hunt the Squirrel has a rich history. The Sleeve notes for Cran’s Dally and Stray CD seem to be no longer available online, but a search around sees it associated with Dumfriesshire and Ayrshire.