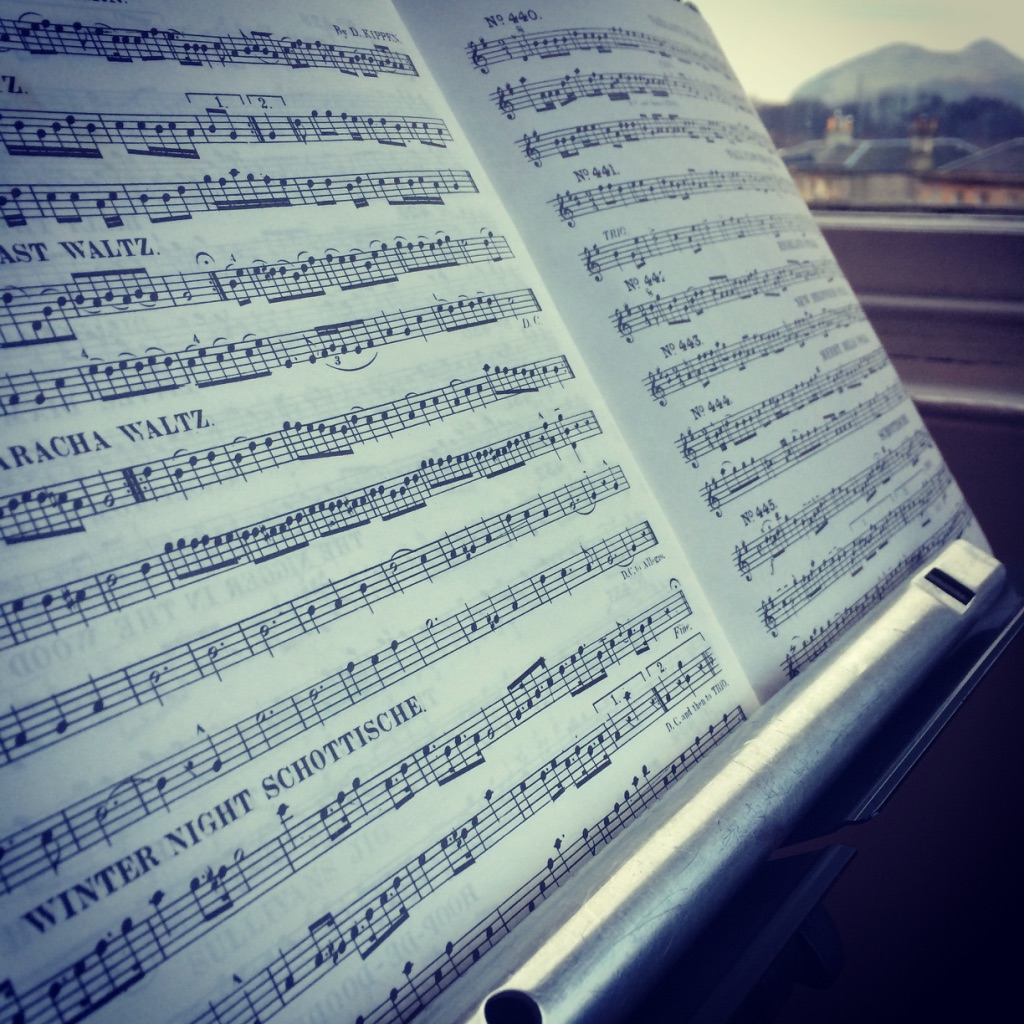

We looked at two tunes, both of which can be found in Kerr’s Merry Melodies for the Violin. Published in the 1870s, they have proved to be an enduring a source for a variety of Scottish, Irish and other tunes common at the time — including popular airs from opera. These tunes would have been an important part of the repertoire of most performing musicians when they were published.

Repertoire

Our tunes were the Schottische/ barndance A Winter’s Night Schottische and the strathspey Gloomy Winter. I also included a reel, Feargan and one of my own compositions, The Slipway.

Recordings of the tunes are below and can be downloaded. I encourage you to listen to them and other versions of the tunes as much as possible to help internalise them.

Update 3 March: A PDF of the tunes has now been uploaded after the server errors were been ironed out. There was some discussion about ABC music notation, an open source music notation system for traditional instruments and repertoire. An ABC version of our tunes has also been uploaded as a .TXT file that ABC apps can read. If you click on the link you should see it in your browser. Find out more about ABC notation here.

A Winter’s Night Schottische I first came across and learned as a barndance from Hammy Hamilton’s recording Moneymusk, where he duetted with a young Paul McGrattan. Hammy Hamilton is a flute player and maker from Northern Ireland, now long resident in Co. Cork. His flutes are excellent but can take some filling and he has both written a guide to the Irish flute and runs Cruinniú na bhFliúit (Flutemeet) every April (some spaces still available at time of writing). Flutemeet was one of the inspirations for our annual FluteFling Scottish flute weekends.

A Winter’s Night Schottische I first came across and learned as a barndance from Hammy Hamilton’s recording Moneymusk, where he duetted with a young Paul McGrattan. Hammy Hamilton is a flute player and maker from Northern Ireland, now long resident in Co. Cork. His flutes are excellent but can take some filling and he has both written a guide to the Irish flute and runs Cruinniú na bhFliúit (Flutemeet) every April (some spaces still available at time of writing). Flutemeet was one of the inspirations for our annual FluteFling Scottish flute weekends.

Flute session in Sandy Bell’s, Edinburgh, November 2016: Cathal McConnell, Sharon Creasey, Rebecca Knorr, John Crawford and Kenny Hadden. (c) Gordon Turnbull

The repertoire or Northern Ireland has many examples of Scottish links and there are a host of strathspeys, for example, that are played as Highlands or barndances. A Winter’s Night Schottische is known in Ireland as Eddie Duffy’s Barndance, Eddie Duffy being a fiddle player from County Fermanagh, honoured in the annual Derrygonnely Festival. I was reminded of this tune after the November workshop when it was played in Sandy Bell’s by Sharon Creasey and Cathal McConnell. Sharon worked with Cathal on the Hidden Fermanagh project and it was Cathal who helped to spread the music of Fermanagh into the wider world. A version of the tune appears in Kerr’s with our title.

For a history of the schottische, a dance once popular throughout Europe, Wikipedia has an overview of its complex history.

The tune has a heavily dotted but regular rhythm, very much akin to a hornpipe and similar to a barndance. There is a fluidity to some of the definitions of these tune types but the dances for them are distinct. Using glottal stops to pulse the breath and push the beat along, there are opportunities to decorate sparsely in the main, but with some variation possible too. We focused on the phrasing to help bring out the overarching structure of the tune.

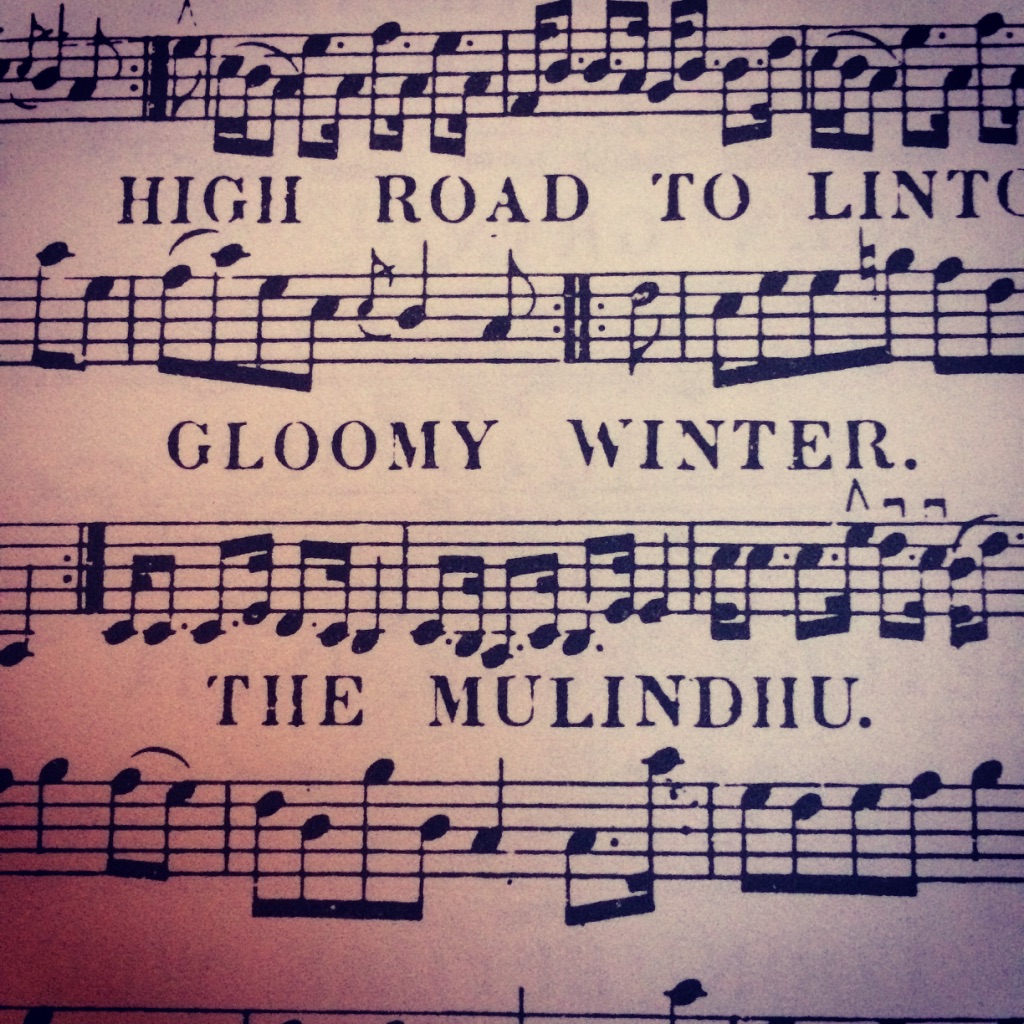

I came across Gloomy Winter in Kerr’s while looking for a companion piece for the schottische. It’s actually a strathspey setting of Robert Tannahill’s 1808 song Gloomy Winter’s Noo Awa’, but should perhaps be more accurately called Lord Balgonie’s Favourite, since that was the original tune that the words were set to. The excellent Sangstories web site has an account of the story behind it. The old tune books have many examples of song airs put to dance tunes.

I came across Gloomy Winter in Kerr’s while looking for a companion piece for the schottische. It’s actually a strathspey setting of Robert Tannahill’s 1808 song Gloomy Winter’s Noo Awa’, but should perhaps be more accurately called Lord Balgonie’s Favourite, since that was the original tune that the words were set to. The excellent Sangstories web site has an account of the story behind it. The old tune books have many examples of song airs put to dance tunes.

Robert Tannahill was a poet, weaver and flute player from Paisley and the inspiration behind the Tannahill Weaver’s name. More about him from the Robert Tannahill Federation.

There are a few settings and titles for this tune, which featured in Michael Nyman’s score for The Piano:

An attraction about the Kerr’s setting in A minor is in the challenges is presents to the flute and whistle. It doesn’t sit neatly under the fingers, drops below the range of the instruments, both holds and pulses on the weaker c’ that also requires tricky articulation. However, this can be used to bring out a sense of vulnerability in the melody, something that Dougie MacLean does with the downward inflections in the phrasing of his version of the song and served as a model for thinking about the phrasing on the flute:

And finally, here’s The Tannahill Weavers playing the song, with Phil Smillie on flute and Lorne MacDougall on whistle:

We also looked at a couple of ways of articulating C natural in particular, leading to a digression that included demonstrations of The Bibble (as played by Ruairidh Morrison and also Munro Gauld) and The Wipe (as played by Phil Smillie and Malcolm Reavell on the whistle)

While looking for final tune to go with these tunes, I came across Feargan (a pet name for Fearghus), a simple but hypnotic reel with a sense of port-a-beul about it. I can’t find much about it at all. As well as being in Kerr’s (1870s), it’s also in the Athole Collection of 1884. Something about the structure of it and the possible meaning of the name makes me think it may be a west coast or Highlands tune originally.

Feargan could go well out of Gloomy Winter as they share the same key. Consider playing it at a slower than usual pace for a reel or possibly even as a strathspey first, then as a reel.

Finally, a bonus tune that we didn’t look at is The Slipway, a kind of slip jig I wrote while playing about with rhythms. I hope you have fun with it.

The next workshop will take place on Saturday 18th March.

We included a refinement that brought us closer to the

We included a refinement that brought us closer to the