The first FluteFling Online event took place in December with a mini-series of workshops led by Claire Mann. The event marked what would have been a weekend event in Aberdeen and attracted a great turn-out, with participants from across the world.

When John Crawford approached me in September and asked what the plans were for the FluteFling Aberdeen Weekend, which usually takes place every November, I confess that my heart sank a little. It was a good question and needed addressing in some way, but it meant that we had to bite the bullet as so many have done and dive into the Online experience.

What did we know about putting on such things? Had we attended any? I personally had shied away from teaching online so didn’t really know what was involved. In addition, so much our working and personal lives are lived online during the pandemic, did we want to spend our spare time wrangling with setups, links and connections? And each of these questions seemed to have others lining up behind them. Wasn’t there online fatigue? Or was that just me?

John has been involved in the FluteFling weekends for many years and has been active in the Aberdeen event too and links up the Aberdeen flute community. He brought in fellow FluteFling supporter Pete Saunders, who has been running the SCaT flute and whistle classes in Aberdeen online this autumn and the technical experience and confidence that was needed. John had also attended a number of online workshops over the summer and had been taking plenty of notes of what worked well.

Over Zoom calls and emails with Sharon Creasey and Kenny Hadden, we realised that it was doable with manageable risks. We quickly identified Claire Mann as a tutor we wanted to involve and with her we were able to shape an event. We all wanted it to be a little different and supportive of those facing the common experience of not being able to meet and play music with others, having to dig deep for inspiration and motivation.

The result was a two-weekend event just towards Christmas. People were unlikely to be going anywhere during the pandemic and we felt that a week between the two workshop days gave people time to work on the material and learning, whatever their commitments. Providing the music and recordings from Claire a week in advance extended the learning focus and we extended it further by including a joint recording project for a video that will be completed soon.

The result was a two-weekend event just towards Christmas. People were unlikely to be going anywhere during the pandemic and we felt that a week between the two workshop days gave people time to work on the material and learning, whatever their commitments. Providing the music and recordings from Claire a week in advance extended the learning focus and we extended it further by including a joint recording project for a video that will be completed soon.

The workshops were timed to be short and focused to avoid fatigue, which meant that they flew by an a lot was packed in as Claire took us through some choices from the online archive of the William Gunn Collection and Shetland reels. The Q&A session became highly technical as Claire responded to questions about rolls, cuts, strikes and alternatives with ease and clarity.

An unexpected development came from those looking to attend from USA and Canada. We had timed the workshops to be either side of lunchtime here in Scotland, but this was still 4 in the morning for some people, or even earlier. To attend at that time was a level of commitment that we hadn’t expected and we responded by recording the workshops and making them available to attendees for several weeks afterwards.

The implication for data protection was a concern and we had to seek consent. However, the way we ran the workshops helped enormously. Pete was a co-host and managed all of the running technical concerns — anchoring the workshops, muting participants and fielding questions through the chat facility. It meant that Claire could focus on the teaching, which was new to her in this setting too. The format was a success and was raised by a few as such in the feedback.

We were quite unprepared for the response, which was overwhelming. With over 70 participants, this was by far and away our biggest event and has caused us all to positively review future plans, including when we all get back together in person.

As participants began joining in the online session, people recognised each other and began chatting and creating a buzz. We have all seen each other on social media, but here we were again, with new faces coming in, some familiar names that are on our mailing lists but are never able attend. People spoke about the friendliness, as visitors from around the world logged in — from a chilly Niagara Falls to Spain, France and Germany. Meanwhile, Claire was in Newton Stewart, Pete was in Aberdeenshire and I was in Edinburgh. There was a definite community feel that spanned the globe.

The recordings enabled people to revisit the workshops and review the learning but also enabled those in California and Japan to be part of the event. Additionally, some people couldn’t attend all of the workshops or had to change plans at short notice, but didn’t miss out. In a non-online situation (IRL – in real life), these people couldn’t have attended or would have lost money or needed a refund.

Our eyes have been opened and while there is no substitute for an IRL experience, this has proved to be a decent substitute with a lot of potential. We are already in the process of organising our next event and what we continue to learn we will be taking into the regular workshops when they are able to resume. Can they be live-streamed or recorded? Or can they be sit alongside our regular events diary? Maybe, maybe.

In the meantime, look out for the video and also for news of our next event.

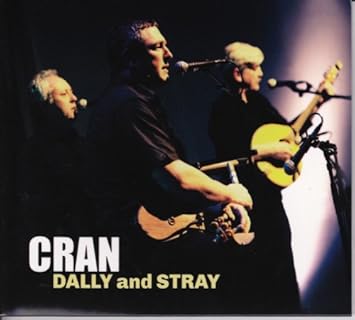

Hunt the Squirrel has a rich history. The Sleeve notes for Cran’s Dally and Stray CD seem to be no longer available online, but a search around sees it associated with Dumfriesshire and Ayrshire.

Hunt the Squirrel has a rich history. The Sleeve notes for Cran’s Dally and Stray CD seem to be no longer available online, but a search around sees it associated with Dumfriesshire and Ayrshire.