John Crawford digs into the digital archives of the Scottish flute world

About the author: John Crawford is a long-standing supporter and co-organiser with FluteFling. John enjoys exploring the forgotten pre-revival Scottish flute manuscripts that reside in online libraries and collections, such as this Scottish fife player’s manuscript from 1799.

About the author: John Crawford is a long-standing supporter and co-organiser with FluteFling. John enjoys exploring the forgotten pre-revival Scottish flute manuscripts that reside in online libraries and collections, such as this Scottish fife player’s manuscript from 1799.

Update: John Crawford has written a follow-up to this post.

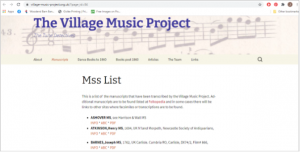

Early in lockdown, I found myself in the Village Music Project (VMP) website. Their primary interest is the traditional social dance music of England and I was intrigued by their Manuscript collection. They’ve transcribed some 45 manuscripts into ABC format with most also rendered as printable PDF documents.

The Village Music Project Manuscript List © Village Music Project

The people who wrote these manuscripts were generally educated and literate people with some available leisure time and a strong interest in music.

The VMP collection includes a manuscript book belonging to Grace Darling’s father and another by poet, John Clare. It’s said that John Clare used to stand in the bookshop, in Stamford, copying the latest tunes from published books into his manuscript book. No doubt, some musicians copied from books owned by better off friends and acquaintances.

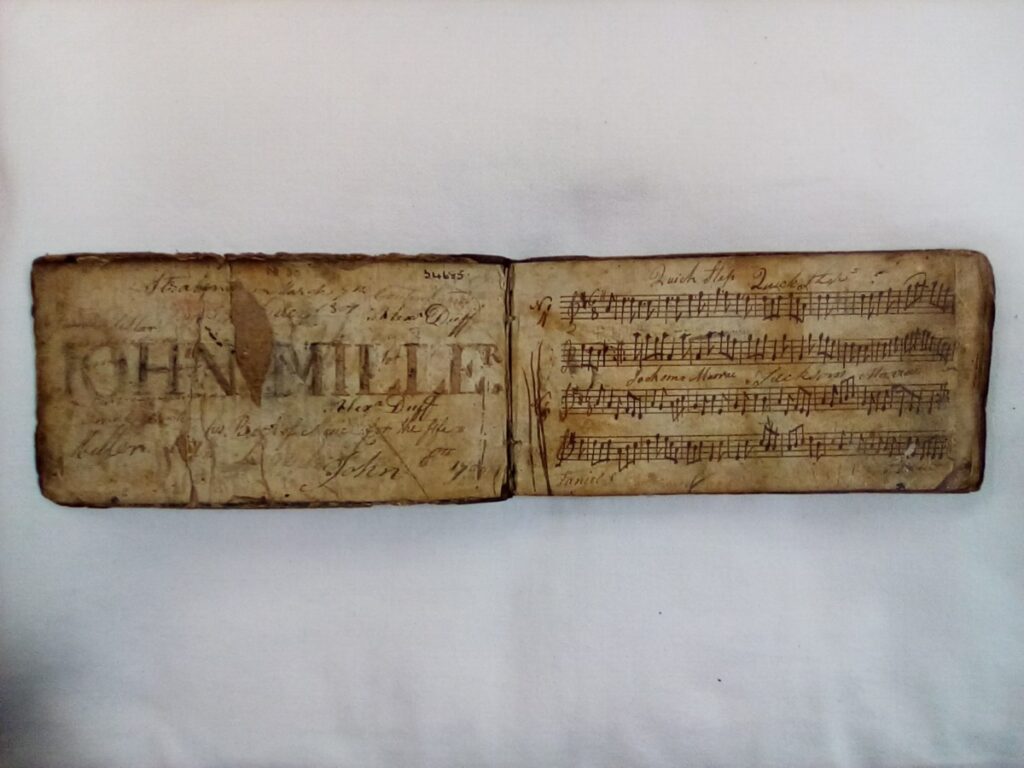

The Scottish location of the John Miller MS, held in the AK Bell Library in Perth, as part of the Atholl Collection, made it the obvious first choice to explore in more depth. I was surprised and delighted when I opened the file and discovered the content was fife music. My first ever flute, nearly fifty three years ago, was a five key, rosewood Bb fife which my friends christened “Roxanne”.

John Crawford’s Bb, 4 key rosewood fife, “Roxanne” (c) John Crawford

The Village Music Project transcriptions and the related notes have provided the opportunity to take a trip back to 1799 into the world of a military fife player.

St Cecilia’s Boxwood C Fife, 1800 © 2021 University of Edinburgh.

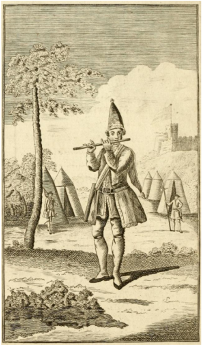

John Miller’s fife would have been far simpler than “Roxanne”. It would have been made from a single piece of wood with six finger holes, an embouchure hole, brass ferrules at the ends and no keys.

St Cecilia’s Hall Concert Room and Music Museum, in Edinburgh, have a boxwood C fife, made around 1800, that is almost certainly similar to the instrument John Miller played. Their website provides more details of the instrument and a sound sample.

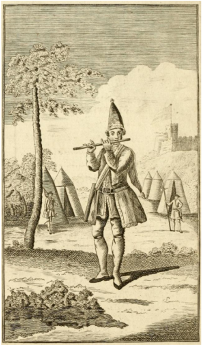

Flyleaf illustration from Thompson’s Compleat Tutor for the Fife – published in 1765 © NLS Inglis Collection.

Chris Partington’s introduction to the VMP material on the MS (see the extract below) provides a summary of the MS contents, some speculation about the man behind it and the context of his fife playing.

The insight we get into the world of a fife player 220 years ago tells us quite a lot about the music John Miller played but relatively little about the context of his playing or indeed the man himself.

The Manuscript

The John Miller MS is in the A.K.Bell Library, Perth, Scotland

This introduction by Chris Partington, village music project, 2002

DESCRIPTION

The John Miller MS is in the A.K.Bell Library, Perth, Scotland, accession number possibly 34685, which is inscribed on the fly-leaf. We have worked from a good photocopy. We do not at present have a context for how the MS comes to be in Perth, other than the obvious martial nature of it and the fact that Perth is I believe the home of the Black Watch.

Music manuscript book, 7.5″ wide, 3.75″ tall, apparently hard – bound. 4 pre-ruled staves per page.

Inscribed (repeatedly) prominently on the flyleaf and elsewhere “John Miller his book of tunes for the Fyfe” often along with dates from August 1799(most often) to 1801. Also postings in Ireland, “Strabane May 12th 1800”, “Stranorlar”, “Londonderry”. Ireland had been and still was in some considerable turmoil at this period……1798 rising, etc. Some of the tunes herein may still have some resonance today, particularly played by a fife & drum band, as it was intended by Mr. Miller.

There are 117 Musical items surviving, at least two pages are missing, the book is otherwise in good condition.

The handwriting is consistent through the book.

It would seem then that John Miller wrote the book, that he was a Fife player, rank unknown, probably in the Regimental Band, but I would not at this stage like to form an opinion as to which Regiment, even if Perth was the home of the Black Watch. Somebody with knowledge of Military History may be able to throw some light on this if they were so inclined.

THE MUSIC

-

- 117 surviving musical items, some barely legible.

- 26 common time marches (or serving as)

- 11 6/8 marches (or serving as)

- 8 jigs

- 4 strathspeys

- 12 reels

- 14 English hornpipes, all well known

- 16 airs

- 1 slip jig

- 25 sacred items, psalms

I would suspect that most of the non-martial and non-sacred tunes would be Lowland rather than Highland in nature. The most remarkable feature to us is the number of tunes marked as being for marches, but this would not be remarkable I suppose for a member of a Regimental fife band.

The Context

Understanding the context of the John Miller manuscript has required exploration of:

- Other music collections including the Buttrey Manuscript and the Black Watch Fife Manuscripts in the NLS;

- Sources on the history of the fife and its place in the music of Scottish regiments (including – Highland Soldier: A Social Study of the Highland Regiments, 1820-1920 by Diana M Henderson; Drum & Flute Duty 1887; Scots Duty – The Old Drum and Fife Calls of Scottish Regiments – Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research Vol. 24, No. 98 ) and

- Sources on the Irish rebellion in 1798 (REBELLION, INVASION AND OCCUPATION: A MILITARY HISTORY OF IRELAND, 1793-1815 – Thesis by Wayne Stack, University of Canterbury 2008)

Each of these topics deserves to be the subject an article on its own right.

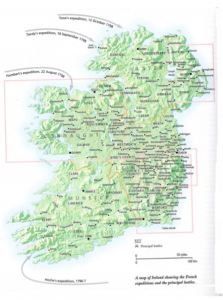

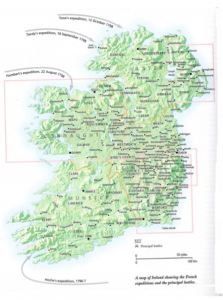

Military activities in Ireland 1798 (c) Wayne Stack, University of Canterbury 2008

Dates and locations given in the MS strongly indicate that Miller was in counties of Tyrone, Londonderry and Donegal during a tumultuous time in Irish history as part of some sort of military unit. The 1798 uprising had just happened. Massacre and atrocities were perpetrated by both government and rebel forces, each feeding on religious bigotry.

The French invasion in August the same year came too late to aid the rebel cause. Dublin Castle accepted the offer of English militia regiments to serve in Ireland, alongside the numerous English and Scottish fencibles units that remained in the country until their disbandment in 1802. In 1801 Britain reclaimed political control of Ireland through the Act of Union.

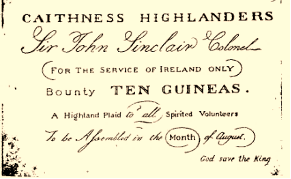

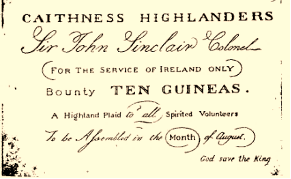

Recruiting card for the Caithness Highlanders 1799 (c) Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research

None of the locations cited in Miller’s MS, other than Londonderry, appears to have been the location of permanent barracks, associated with a specific regiment. Londonderry seems to have been the location of a Militia barracks. Evidence supporting the VMP suggestion that Miller might have been part of what was to become the Black Watch is very limited. There is no clear evidence that the 73rd (Perthshire) Regiment of Foot, or the 42nd Regiment of Foot, were in any of the locations mentioned by Miller on the dates indicated in his MS.

An alternative possibility is that Miller belonged to one of the Scottish fencibles regiments. These were raised as a defence force during 1793/ 94 due to the fear that the French would either invade Great Britain or Ireland, or, that radicals within Britain and Ireland would rebel against the established order.

A significant number of the Scottish fencibles served in Ireland including the Breadalbane Regiment (Embodied in Perth in 1793 – 3rdBn disbanded in Ayr in 1802) and the Angus –shire Regiment (disbanded in Perth in 1802). It’s interesting, and perhaps not entirely coincidental, that Miller’s MS has no postings or dates after 1801.

The possibility that Miller was part of an Ulster militia regiment seems to me less credible.

The Content

The Atholl Collection Catalogue (c) 1999 Perth and Kinross Libraries

The original copy of the MS, in the Atholl Collection, has not been digitised. It is of course, possible to visit the Bell Library in Perth to view the manuscript. Naively, I thought when the pandemic is over it’ll be relatively easy to go to Perth and see this at first hand. Here we are a year later still waiting.

The Collection, consisting of around 600 books and manuscripts of Scottish music, some from the seventeenth century, has been described as one of the most important collections of its kind in existence. In addition to the Miller manuscript the collection includes 50 other flute specific items making a visit to the Bell Library well worthwhile.

A catalogue was published in 1999 and is available from the library service at a cost of £4.95 plus postage. A card index to the tunes has been compiled by a volunteer and this is currently being transferred to an Access database. Contact the library if you are looking for a particular tune. info@culturepk.org.uk

There are two main options for accessing the manuscript online. The first is via the Village Music Project website: The VMP manuscript list is at this link. The MILLER,John MS, 1799, is item 32 in the list. The following links will take you directly to an introduction to the manuscript and the tunes in ABC and standard music notation respectively.

INFO * ABC * PDF

The second online access option is to use Richard Robinson’s Tunebook . The following link will allow you to see the entire Miller MS in standard notation:

http://richardrobinson.tunebook.org.uk/documents/0/11/112.html

The links associated with each tune provide download options including ABC files, a printable PDF of the tune in standard notation and a MIDI file.

My own favourite tunes from the manuscript include:

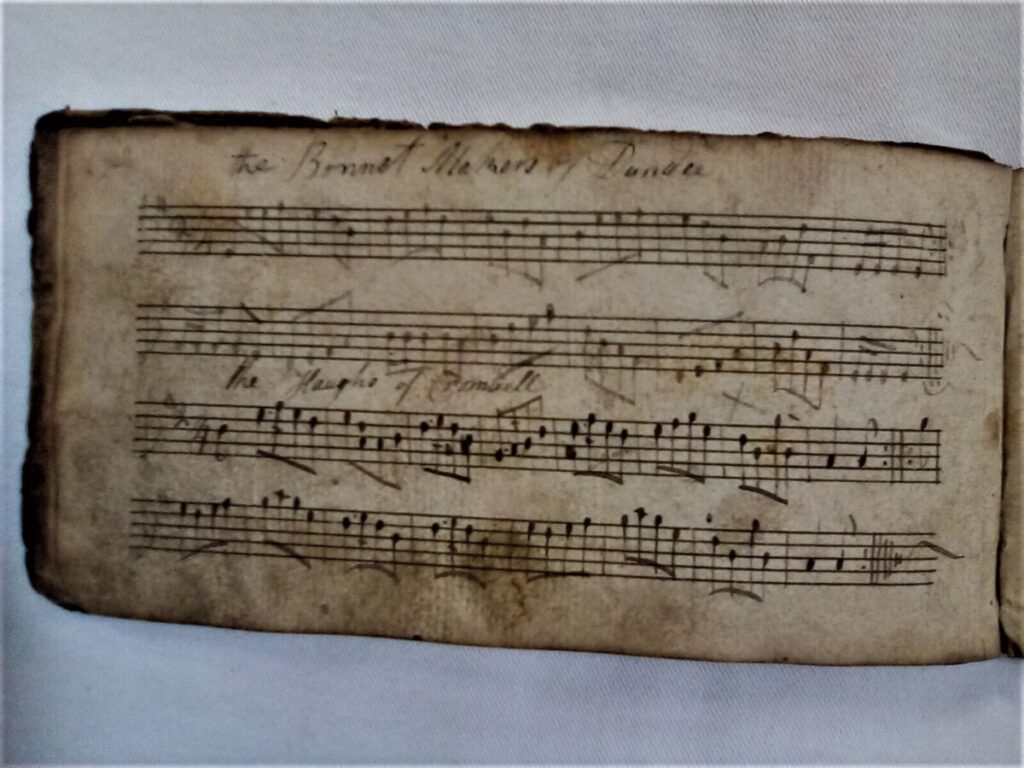

- JMP.019 – The Bonnet Makers of Dundee (Bremner’s 1757 collection)

- JMP.026 – The Sussex Polka (untitled polka from the 1796-1818 MS collection of William Aylmore)

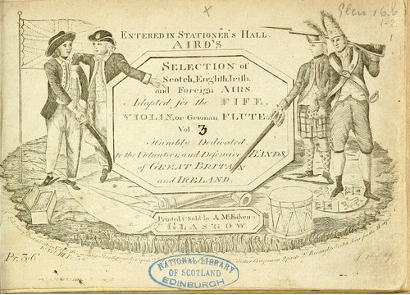

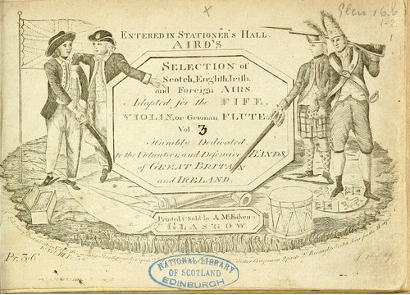

- JMP.015 – Quick March [aka “Auld Reckie”, or “Hoble about”] (Aird – Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, vol. 3 1788) Note the dedication on the cover! “Humbly Dedicated to the Volunteer and Defensive Bands of Great Britain and Ireland”

- JMP.062 – West’s Hornpipe (Appears in Preston’s Twenty-Four Country Dances for the Year 1798. The tune also appears in the Buttrey fife manuscript. This tune is now a regular fife and Lambeg drum repertoire)

Cover of Volume 3 of Aird’s Collection published in 1878 (c) National Library of Scotland

Although this is only a small sample from the manuscript, it does support a view that Miller’s had a source that had access to contemporary music collections, like Aird’s, Bremner’s and Preston’s published in the late 1700s.

Another feature of the manuscript is the number of tunes (like West’s Hornpipe) that are now part of the Orange Order fife and drum tradition.

Cover of With Fife and Drum by Gary Hastings (c) Gary Hastings

Perhaps this isn’t surprising; in the late 1790s Orangeism quickly spread in the North of Ireland; by early 1797 as many as 30,000 Orangemen had enlisted in Ulster yeomanry corps. Miller, and his regiment, must have found himself in the middle of a society where Protestant/ Orange Order values were very influential.

Other tunes in the MS that currently feature in the music of Orange Flute bands include:

- Boyne Water

- Croppies Lie Down

- Morning Stare (Star)

See Gary Hasting’s excellent book With Fife and Drum for more details.

In common with the contemporary Black Watch & Buttrey fife manuscripts, the Miller MS omits the duty tunes that would have regulated the soldier’s day (The Reveille, The General, to Arms, the Gathering, the March, the Retreat and the Tattoo). Presumably, as part of the fabric of regimental life, no written reference to these was required.

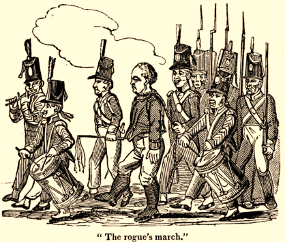

An 1819 political cartoon (c) Wikipedia.org

Only the Buttrey MS includes “The Rogue’s March”; arguably the most recognised melody in martial repertory of the era. Being “drummed out of the regiment” consisted of as many drummers and fifers as possible, playing the tune, parading the prisoner in front of the regiment. The offender’s coat would be turned inside out as a sign of disgrace. The final ignominy was a kick from the youngest drummer followed by ejection through the barrack’s gate with an order never to return.

Some of the available manuscript resources suggest that the musicians who played for marches and parades would be the same ones playing for social events and dances in the officer’s mess and the Sunday morning church parade and service. Other sources dispute this; making the point that the drums and fifes were part of the regiment. The fifers were generally boys. Some were the sons of soldiers who were brought up in the regiment, regarding it as their home. This is unlikely to apply to Miller if he was part of a short term fencibles regiment.

As the Buttrey MS confirms another recruitment path, for fifers, was via the poor house or, other comparable institutions. In contrast, the regimental bands were civilian professional musicians, in uniform, sponsored by the officers of the regiment. Ironically the band uniforms were often more exotic and elaborate than those of the drums and fifes.

Who was John Miller, what regiment was he part of, where, when and how was he recruited, where did he obtain the tunes in his MS book, why did the book have a four line stave, how did he obtain his skills in playing the fife and writing music notation, who did he play music with and in what circumstances? The answer to these and a host of other questions may lie in a closer examination of the Atholl Collection or, may be lost to us forever. His music though is still with us thanks to his manuscript and deserves to be remembered and played providing an insight into our musical history.

Update: John Crawford has written a follow-up to this post.

An 18th Century British Army fife player practicing (c) militaryheritage.com (additional text by John Crawford)

Article (c) John Crawford 2021