FluteFling NE Tunebook Project: 09 Pipe Major Jim Christie of Wick/ The Rose Amang the Heather/ Bonnie Kate o’ Aberdeen

A session at the Dalriada at Edinburgh FluteFling 2019. L-R Munro Gauld, Harry Mayers, Malcolm Reavell, Melanie Simpson, Orin Simpson (c) Gordon Turnbull

This ninth video in the series features three tune types – a march, strathspey and reel.

For background to the project of 10 sets of tunes being recorded over 10 weeks, and to see the first video, start here. Alternatively, go straight to the videos on my Youtube channel.

You can download the free PDF of the sheet music here:

FluteFling Aberdeen 2019 NE Scotland Tunes

Wick to Aberdeen Over the Heather

FluteFling NE Tunebook Project: Pipe Major Jim Christie of Wick/ The Rose Amang the Heather/ Bonnie Kate o’ Aberdeen

This ninth video in the series features a march, strathspey and reel, all associated with the North and North East of Scotland. These are from the FluteFling NE Tunebook of Scottish session tunes for flute and whistle and I play these on my Rudall and Rose 8-keyed flute in D.

Pipe Major Jim Christie of Wick

Pipe Major Jim Christie of Wick was written by Wick fiddler Addie Harper. Apparently one of Addie Harper’s earlier compositions, it sits neatly in the bagpipe scale and suits flutes and whistles well too. I find the structure encourages a pulse of breath that makes it flow along readily. Look out for variations in the deployment of snaps in the melody.

The Cape Breton fiddler Buddy McMaster helped to popularise this tune in Canada and The Traditional Tune archive has some background information on the composition.

For more background on Jim Christie, who founded a girls’ pipe band during WW2, there’s a good account of his life here.

The role of Pipe Major is explained in this Wikipedia entry.

Update: Munro Gauld (pictured, above) was in touch about this tune, with helpful information on different versions and background. In particular, he points out that the version in the NE tunebook is not a common one in Scotland and is usually played in 2/4 time with 4 parts. He said,

It’s a tune I know well as it was a staple of the Plockton session when I lived up north 20 years ago, here in Dunkeld it’s also played most weeks at the session and wherever there is a session with a Borders / lowland / cauld wind piper, it usually gets an airing. But it also makes a great fiddle tune. And once you’ve got the hang of articulating the Strathspey-like dotted notes and octave jumps, it’s great fun to play on the flute.

But looking at the NE Tune book version – I’ve never seen it / heard it played as a 4/4. Any time that I have ever heard it played (or played it myself) it is always as a 4-part 2/4 pipe march (as written for the pipes).

Munro illustrated this by sharing a Pipe band version:

Additionally, here’s a session-like version played by a young fiddler in Wick, Addie Harper’s home town.

Munro continues:

It would seem that the version in the NE Tunes book is taken from the playing of Buddy MacMaster (as found on the Trad Tune Archive). Obviously when it travelled with him over the Atlantic it got smoothened out from its 2/4 Pipe March roots to more like a 4/4 reel. Having said that, I couldn’t find a recording of Buddy MacMaster playing it online, so I may be wrong. I did find this fiddle version from Gus Longaphie from (I think) Prince Edward Island which might give an indication of how Buddy MacMaster plays it.

I’d suggest that perhaps, in a Scottish context, the Cape Breton version of the tune is an outlier – and not one that would be commonly played in Scottish sessions. In your Blog it might be worth mentioning this and if you can easily find it, put in a link to music for the 4-part 2/4 Pipe March version.

Munro adds,

Note that the third and fourth parts are both quite tricky – but lovely to play on the flute.

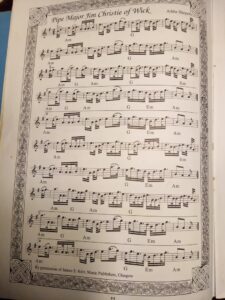

PM Jim Christie of Wick as published in Ceol na Fidhle, published by Taigh na Teud Music Publishers.

This is a good reminder of how things are often not straightforward in traditional music, with different versions and origins often sitting side by side. This is true, even when the composer is known and the music is published, and my thanks to Munro for drawing attention to this.

From my own perspective, I was surprised that the pipe march only had 2 parts, when 4 is more common. Now I know why.

Munro illustrated the 4 part version with a photo (opposite) from the excellent Ceol na Fidhle music book series published by Taigh na Teud Music Publishers based in the Isle of Skye, edited by fiddler Christine Martin. It can be found in the combined Book 3 and 4 edition and I can recommend these and the related books. To see a list of some publications that have been helpful to us in FluteFling, check out the Resources page.

The NE session sets tune book was compiled by John Crawford from existing session material to be found around Aberdeen music groups. The 2-part version allows us to also play with Cape Breton musicians and there is now an opportunity to broaden the repertoire by adding in the additional parts so that we can play with others. I’ll be adding a bonus video of the 4 part version at the end of this project.

Uncertainty about origins and versions is a big theme for this set of tunes and illustrates the folk process in action.

The Rose Amang the Heather

The Rose Amang the Heather is a traditional strathspey in D. It is known by various titles and was taught by Tom Oakes in 2021 as a Northumbrian tune, The Kielder Schottische. I learned it as The Laddie wi’ the Plaidie and it is a good example of a tune that happily exists in different traditions (link to The Session).

The Traditional Tune Archive gives a different, but related, 2-part tune for The Rose Amang the Heather, from The Middleton Collection of 1870.

However, a search for The Lad wi’ the Plaidie reveals a 2-part version from 1910 and a more elaborate 5-part strathspey, 3 of which are the same as our version.

For comparison, here is The Kielder Schottiche from The Session.

And here’s a recording of Tom Clough (Northumbrian pipes), Billy Ballantyne (piccolo) and Ned Pearson (fiddle): https://youtu.be/rrQaMMjCczA

I suspect that it is Scottish in origin and originally in two parts, but completely take on board Tom’s assertion that it is Northumbrian. Many tunes are common to both Northumbrian and Scottish traditions as each repertoire leaches over the Border.

In addition, the running triplets in the third part are a strong feature of hornpipes beloved of Northumbrian pipers and others. Harvest Home and The Belfast Hornpipe are two notable and well-known tunes that feature this. However, triplets and quadruplets are also common in strathspeys, which are often played at a hornpipe tempo.

I’ll leave it there with regards to this tune, but in my opinion, Northumbrian pipers’ tune books are generally a rich resource for flute and whistle players exploring different settings of Scottish material. Cross-Border hybridisation is clearly a long and noble tradition and there are many threads to the heritage of this lovely tune.

The three part version is the one I have come across the most and it certainly fits the flute and whistle well. Be sure not to let the triplets run away, find a space in the music to breathe and keep it steady.

Bonnie Kate o’ Aberdeen

Bonnie Kate o’ Aberdeen is a reel in Em and has its own questions regarding origins. A tune and a country dance by that name were published in 1771 by Thomson, but the melody, also known as Bonnie Kate, is different. After a bit of hunting around with little success, I tried playing the tune into the Tunepal app.

Tunepal is a cloud-powered app developed for traditional musicians by Bryan Duggan and his team. It is available for Android and Apple phones, as well as online. After playing a 12 second clip into the app, it will search the free online databases and suggest matches with different degrees of confidence. For any musician trying to identify a tune from a fragment, maybe heard or recorded in a session, it’s a really valuable tool.

Tunepal suggested an Irish reel, called The Mountain Lark, which I have heard but don’t play. A search on The Session reveals that there are two tunes with that name, both in the same key, but distinctly different from each other. One of those is our version and lesser known.

The tune also has a couple of alternative Scottish titles – The Rakish Highlander and Bonnie Kate o’ Aberdeen. Additionally, the annotation to The Rakish Highlander in The Traditional Tune Archive discusses the interest in Scottish repertoire to Irish fiddlers.

On The Session page linked above, FluteFling’s own Sharon Creasey, aka The Archivist and a specialist in Fermanagh music and older manuscripts, writes:

This tune is in the Gunn Book (Fermanagh 1865) as Boney (sic) Kate of Aberdeen.

What a great tune!

The Gunn Book predates Ryan’s Collection (1883) by almost 20 years and strengthens a Scottish claim.

Sharon herself reintroduced the to Aberdeen, teaching it in her workshops, and hence into this PDF. I’m not aware that the tune is otherwise known in Scotland currently.

From Scotland to Ireland and back again with this reel, a Northumbrian schottische or a Scottish strathspey for another tune, from Caithness to Cape Breton and back for our march. Whichever way you look at it, the connections and cross fertilisation of people, culture and music makes the world a richer place.

Ten weeks of videos

Over a 10 week or so period, I am recording and uploading to YouTube a set of tunes from the PDF roughly once a week. The aim is to introduce the tunes, point out some techniques along the way and then play them as a set as I might play them in a session.

As I go along, I’ll take in suggestions to improve the sound and presentation and get back into the way of teaching again. There is an in-built slow down function in YouTube and the PDF is available to everyone, so why not join me on the journey?