This week’s tune is The Belfast Hornpipe, a three part tune with some technical challenges that has in its time been a showcase tune.

Hornpipes

Hornpipes are an unusual type of tune that form a smaller part of the repertoire than jigs, reels, strathspeys and marches, certainly in Scotland. However, they are an old form of tune, perhaps originally in 3/2 time which can still be found in tunes from Northumberland and the Scottish Borders.

An introduction on Wikipedia explains the different sorts of hornpipe quite neatly. There is a relationship with some Scottish reels as well. Loch Leven Castle is a Scottish reel that we covered a while back and is known in Ireland as a hornpipe called Tuamgraney Castle. Hornpipes seem to be related to barndances, and some long dances or set dances and clog dances too, so playing hornpipes is a way into those less obvious tunes.

Here’s the famous Alla Hornpipe in 3/2 from Handel’s Water Music, dated 1717:

Here’s footage from 1963 of John Cullinane, from County Cork step dancing the Liverpool Hornpipe; Seán O Cearbhaill from Limerick on the fiddle & looking on are the members of the Tulla Céili Band.

And here’s the version of the Belfast Hornpipe played by The Dubliners that was the inspiration behind the request to look at this tune, a very different way of playing:

Our version of the tune comes from Miles Krassen’s edition of O’Neill’s Music of Ireland. This is the controversial “updated” version of the 1,850 tunes collected in the early 19th Century by Captain O’Neill of the Chicago police. An ABC version of the original book can be found on John Chamber’s web site. You may be able to get the original from music shops in Edinburgh or online at Custy’s Music Shop (Ennis, County Clare), Walton’s (Dublin) or even Amazon (I have a shop). If you’re not sure, check with me first.

We play the tune with a dotted rhythm (long-short) and hornpipes are often played this way, although not always notated so. Try putting more breathe on the beat (the longer notes) to help generate a pulse. This is useful practice for reels.

Much of the melody sits on a series of broken chords and this is the key to understanding where the fingers go because the direction at times seems counter intuitive. Many hornpipes became showpieces for technique and this is most apparent in the third part, which consists of strings of descending triplets. Beware speeding up here, which is very common. Instead, try to focus on the underlying sense of the tune by substituting triplets with the main notes; in ABC notation, this means

| 3(fgf 3(ede 3(ded 3(cdc |

becomes

| f2 e2 d2 c2 |

Once you have this secure in your playing, introduce the triplets once more and it should be easier to maintain the rhythm (emphasise the first of the triplet notes with more air) without the tune running away under your fingers.

Although we had no problem with finding space to breath, if you wish to do so it is possible to play the first note of the triplet and drop the remaining two. Having done the previous exercise it should be possible to do this without too much thought.

Finally, we considered how much air to give the triplet runs. While there is a practical consideration to gradually decreasing the volume of air over the phrases — and running out of air is another reason why people speed up on this — there is a more compelling musical reason too as it adds contrast to the passages. Hornpipes can sometimes be dramatic and stagey, which may be related to their popularity in the 19thC.

The Resources page has music and recordings for the tune.

Hornpipe titles tend to be a little apart from those of other tune types. They might celebrate ships (The Great Eastern, The Great Western, Royal Belfast) as well as more far-flung places (Off to California, The Saratoga Hornpipe), which are also celebrated in ship names and reflect the expansion of the western world during the 19thC. The Belfast Hornpipe has a few names too: http://www.tunearch.org/wiki/Belfast_Hornpipe_%281%29

Vernacularisms

On the subject of Belfast, concertina player Jason O’Rourke writes short stories that draw inspiration from his observations of Belfast life and is highly recommended. If you’re ever in Belfast, you may be lucky enough to catch one of his Vernacularisms walking tours that takes you to the locations in which the stories are set. He’s also a dynamic musician.

Main photo: mural collage from the Household Festival, Belfast 2013 (c) Gordon Turnbull

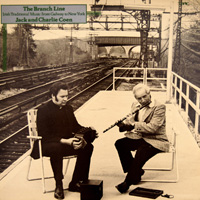

I was surprised to discover that not a great deal is known about the tune. It is associated with Irish-American fiddler Larry Redican (more on him here) and bore his name on some recordings, notably by Bobby Casey (1959) and the Coen brothers’ The Branch Line. No, not the movie makers, but Jack and Charlie from east Galway, playing flute and concertina.

I was surprised to discover that not a great deal is known about the tune. It is associated with Irish-American fiddler Larry Redican (more on him here) and bore his name on some recordings, notably by Bobby Casey (1959) and the Coen brothers’ The Branch Line. No, not the movie makers, but Jack and Charlie from east Galway, playing flute and concertina.