This gallery contains 20 photos.

Some more photos from the Aberdeen FluteFling weekend November 2024 See the blog post about the weekend here. Click on the photos to enlarge. Credits: Linda Harkness, Gordon Turnbull; captions to follow.

This gallery contains 20 photos.

Some more photos from the Aberdeen FluteFling weekend November 2024 See the blog post about the weekend here. Click on the photos to enlarge. Credits: Linda Harkness, Gordon Turnbull; captions to follow.

John Crawford, Euan Reid, Kenny Hadden and Sharon Creasey at an outdoor session at Stonehaven. (c) Gordon Turnbull

Getting back into in-person events was never going to be easy, but we knew we had to launch the tunebook at some point. We couldn’t have chosen a better way, than at the 33rd Stonehaven Folk Festival. Just south of Aberdeen, it is a long established landmark festival in Scotland. With a number of artists appearing that included the flute or whistle — Flook, Rura and Deira from Asturias, it was definitely a good match.

Sharon Creasey, Kenny Hadden and myself, with John Crawford and Peter Saunders, had begun thinking about this last year but found it tricky with Covid levels being so unpredictable. Thinking about how we might have to manage an in-person event in such a climate was difficult. When I looked in January, there were still restrictions on room capacity and requirements for mitigation. The rules changed but could have changed again by the time we had responded. FluteFling is run in people’s spare time and there were organisations with full time staff who struggled, so it wasn’t going to be simple.

On top of that, we were collectively no longer used to playing in sessions, performing and teaching. I think I hadn’t taught for 2 years and certainly hadn’t played on stage for 3 or 4 years. There were steep relearning curves whichever way we looked. So Kenny approached Stonehaven organisers Charlie West and Meg Findlay knowing that we needed a bit of help.

To their credit, they understood the situation and used their experience to make it straightforward. The festival was only just returning after having to cancel the last two years and the performers that weekend were rebooked from the 2020 weekend that didn’t run. Clearly, trying to get back to the things that matter to us was a theme of the weekend.

John Crawford completed the necessary risk assessments for the workshops and he and Pete Saunders were volunteering, so we were well looked after and it was less to think about.

The weekend was set to be a sunny one and we set our stall and new banners up in the hot and sometimes busy bar in the Town Hall on the Friday evening. Coralie Mills had kindly volunteered to run the stall, the new banners drew attention and the contactless machine was soon doing its business as we drew some friendly attention and began selling our first copies.

Having worked on this for over a year, largely in lockdown, it was difficult to gauge what kind of response the book might have. Sharon in particular had shaped it with the contributors and we could see a value in it that we hoped others would recognise. So it was gratifying to see the response from all musicians, not just flute and whistle players. Thank you to everyone who took the time to speak to us about it over the weekend.

The stall was in the bar upstairs from the concert hall and we able to quietly nip in and out to the balcony and watch some of the performances in between catching up with each friends we hadn’t seen in person for a while.

Flook were in fine energetic form and, as expected, extraordinarily tight and focused. We had put up a signed copy of the tunebook as a raffle prize and were bowled over to discover that the whole band had supported us by adding their signatures. Somebody walked away that evening with quite a special prize.

The Saturday workshops at Dunottar Primary School were low key and with a friendly and helpful Janny and volunteers we were quickly set up. The morning workshops were beginner flute (Kenny Hadden) and beginner whistle (myself and Sharon Creasey). It was the first time that we had tried two tutors in one workshop, but it meant that Sharon and I could address individual issues and compare notes as we went along — it’s always good to hear different perspectives on the same subject.

In the afternoon, Sharon took an advanced whistle class while I took the flute class. Everyone was at different stages of returning to playing music again — some had not played for months, some had not been in sessions, others had happily been playing away in person or online. It was tricky to get the balance right, but we all had to begin somewhere.

Returning to teaching after a gap of 2 years was also a personal challenge. There was lots of talk and questions and in the back of my mind, I could hear Hammy Hamilton’s comment from Cruinniú na Bhfliúit, that he was always happy to hear talk coming from a room because it meant that people were discussing questions rather than simply learning tunes. As David Fednandez said, he was just happy to be back with others again playing the flute.

Straight after the workshops, Kenny and I did a performance spot in the marquee in the square. We played some of our tunes from the book, including a duet. As many musicians elsewhere had said, it was good to get back to performing. Some of it felt familiar, other parts a bit alien after the last few years, but the sound was good and the audience enjoyed it.

The Asturian band Deira followed us on stage and were complimentary. As we dashed across the road to the book launch, their amazing sound rang out across the square and I made a mental note to try and hear more of them.

Kenny Hadden giving a talk at Stonehaven on the revival of the flute in Scottish traditional music (c) Gordon Turnbull

In the function room of No. 44, around 50 people had gathered to hear Kenny, who had set himself up to give an illustrated talk on the revival of the flute in traditional Scottish music.

With a big display screen and good sound, his meticulous trawl through the archives was an expansion on his essay in The FluteFling Collection that had people talking afterwards.

I think most people learned something new and to others it was a complete revelation. There were good questions from an engaged audience afterwards and I hope that there will be other chances to hear Kenny present this again.

Kenny, Sharon and myself followed the talk with a short recital of our own contributions to The FluteFling Collection. Peter Saunders was there and you can hear some of the performance on Peter’s YouTube channel:

An Aberdeen-based Polish whistler and David Fernandez at the book launch session. (c) Gordon Turnbull

There was a short session afterwards and friends were able to catch up with each other. Somehow, there’s never enough time to do everything we would like to do.

We were fortunate in that the Festival had donated the space to us and provided a sound technician to help set us up. With pubs and bars filled with music across the town, we also our own space to play and could hear each other.

The bookstall still needed manning and people were getting hungry after a long day

I managed to catch Deira perform after the launch. The trio have a tight and driving sound that reminds me of Rura, but playing traditional Asturian and original tunes with a creative use of live loops and effects.

It’s easy to see how they went down well at Celtic Connections just before the pandemic and I recommend checking them out.

We ended up taking fish suppers to the splendid boardwalk that runs along the shore. A tune was soon struck up and we were joined by the Paddy Buchanan Band who had done a great performance on the Friday night. It was a fine evening to cap a fine day.

On Sunday, we took some time to tie up the loose ends, drink coffee and reflect on the launch, thinking of what happens next.

There was such a buzz from being with people again, many of whom we hadn’t seen for a couple of years, and playing music together. The support and goodwill towards FluteFling was overwhelming, so thank you to everyone who helped to make it happen and to those who managed to attend.

Our thanks go to the organisers for accommodating us and making us feel so welcome. This was most certainly a case of a bigger organisation being true to their roots and seeing the opportunity to give a helping hand to a smaller organisation such as ourselves to get going again in the post-lockdown world. We were able to provide workshops in return and so the benefit was mutual and we would consider similar arrangements in future.

Our thanks too, for Tasgadh for the grant and support that enabled the publication of the book in the first place and to the amazing contributors who were so keen to be part of this project. To order your own copy of The FluteFling Collection in Print or eBook format, visit the FluteFling Shop.

It was a memorable weekend and we resolved to have a similar event in Edinburgh. Covid and personal circumstances have delayed this, but we all look forward to the next one. Sign up to the newsletter to hear about it first.

About the author: John Crawford is a long-standing supporter and co-organiser with FluteFling. John enjoys exploring the forgotten pre-revival Scottish flute manuscripts that reside in online libraries and collections, such as this Scottish fife player’s manuscript from 1799 held in the A K Bell Library in Perth. The manuscript is part of the Atholl Collection, a key archive source for the Scottish flute world.

About the author: John Crawford is a long-standing supporter and co-organiser with FluteFling. John enjoys exploring the forgotten pre-revival Scottish flute manuscripts that reside in online libraries and collections, such as this Scottish fife player’s manuscript from 1799 held in the A K Bell Library in Perth. The manuscript is part of the Atholl Collection, a key archive source for the Scottish flute world.

Part 1 of this article dealt with my early lockdown experience, pursuing the John Miller Fife MS (manuscript) I found in the Village Music Project (VMP) website. This revealed a lot about the music John Miller must have played on his fife and provided a partial understanding of the context of the manuscript, but largely left Miller and his life shrouded in mystery.

The trail to the original document pointed to the Atholl Collection and the AK Bell Library in Perth. The collection was compiled by Lady Dorothea Murray, later Ruggles-Brice, and a daughter of the 7th duke of Atholl. When she died she left instructions for it to be bequeathed to the Sandeman Library in Perth. When this closed the Collection moved to the AK Bell Library.

The general significance of the Collection has been outlined in part 1 of this Blog. The catalogue, compiled by Dr Sheila Douglas, confirms the Atholl Collection has been recognised for many years by the world’s academics, with enquiries from institutions as diverse as Harvard, the Joseph Hayden Institute in Cologne and the University of Sydney. It remains an open question whether Scottish traditional musicians have invested an appropriate level of interest in understanding the value of the collection and what it can offer them.

From a flute perspective it’s worth re-emphasising its significance in the Collection. The Miller MS is one of 60 items where the catalogue description specifically mentions flutes or fifes. This is a powerful demonstration of the popularity of fifes and flutes in the 18th and early 19th century and makes a strong case for further study of the collection. Items of note and interest include:

At the time of writing the Miller MS, along with the rest of the collection, has not been digitised, making a visit to Perth essential. When Part 1 of this blog was written COVID restrictions made it impossible to see the MS at first hand and examine it in more detail.

Waiting another six months to see the MS was a challenge and a time to remember one of my mother’s favourite Gaelic proverbs about patience:

“Am fear a bhios fad aig an aiseag gheabh e thairis uair-eigin.”

[He that waits long at the ferry will get over some time.]

On Friday 10 September 2021 I finally made it to A K Bell Library to see the MS. Was it worth the wait? The answer is an unambiguous and absolute yes. I enjoyed my day immensely. Being able to see, and touch, the MS was a very powerful experience. I felt very privileged and had a very strong sense of being in direct touch with history. Probably the nearest parallels are:

The experience was amplified by:

Seeing the MS sparked some additional ideas about how the MS originally came into being and what might have happened to it, between John Miller’s time, and it becoming part of the Atholl collection. The handwriting of the tune titles is very precise and stylised; certainly the hand of a highly literate well educated individual. There’s evidence of a second less literate, less well developed hand, in pencil, in additional notation in the book.

I’m now wondering if it’s possible Miller got the book from his Bandmaster and that the second, less literate hand writing is his. Given the lack of history of the MS and how it came into Lady Dorothea’s hands it is, of course, equally possible the other handwriting is that of an interim owner.

My conversation with the library staff during the visit flagged up the material on the adjacent shelves relating to the Black Watch. The Village Music Project narrative relating to the MS, speculates that Miller might have been associated with the Black Watch or its antecedents (the 73rd (Perthshire) Regiment of Foot, or the 42nd Regiment of Foot).

My initial online research had failed to find any indication that the Black Watch, or its antecedents, was in Ireland, at any of the locations mentioned in the Miller MS (Strabane, Stranorlar and Londonderry) between 1798 and 1801. This finding appears to be supported by the additional material I found in the Library.

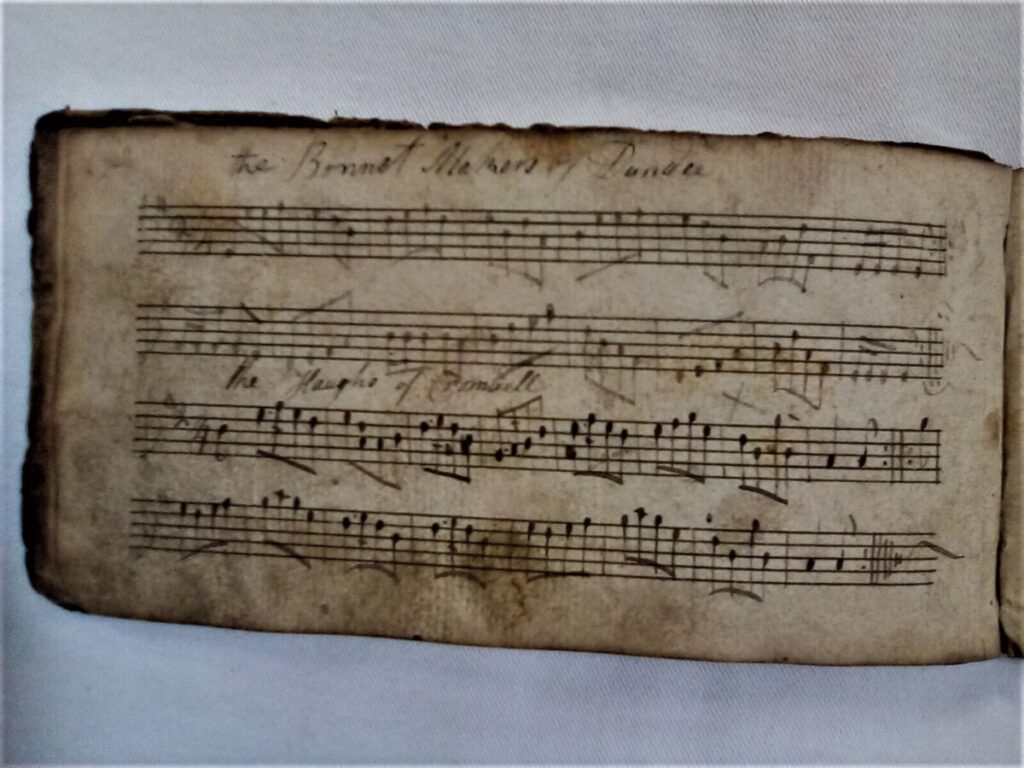

The John Miller manuscript with the tunes Bonnet Makers of Dundee and the Haughs of Cromdale (c) John Crawford.

My view, based on the information currently available, is that it’s much more likely Miller was part of the many Fencible regiments formed and posted to Ireland in the wake of the 1798 uprising and the French invasion. Unfortunately attempts so far to uncover historical sources providing detailed information on recruitment by these Fencible regiments, their bands and musicians appears to be very limited.

Perhaps this is unsurprising given the limited time these regiments existed for. The earliest regiments were raised in 1759. When it became clear that the rebellion in Ireland had been defeated and that there would be peace between France and Britain in 1802 (The preliminaries of peace were signed in London on the 1st of October 1801) the Fencible regiments were disbanded.

We may have to accept that John Miller’s history is lost to us and that we can only speculate about his age and circumstances; how he came to be recruited; what regiment he was part of and how his MS came to be part of Lady Dorothea’s collection. The repertoire in the MS suggests a Scottish connection but this is not 100% conclusive. The Buttrey Manuscript mentioned in my previous post includes a wealth of Scottish tunes. John Buttrey joined the 34th Regiment in Lincolnshire, England in 1797 as a drummer at the age of 13. He served in Africa and India and was discharged when he returned to England in 1814.

John Miller’s MS is, nevertheless, an invaluable and rather unique window offering a more human perspective on the importance of the fife in the life and music of Scottish Regiments in the 18th & 19th century than formal sources like Thompson’s 1765 Compleat Tutor for the Fife with all its duty calls. These are tunes that deserve to be played; when you do, tip your hat and say thanks to John Miller.

Scots Guards band in the Park in 1880 by Édouard Detaille. Note four ranks of fife players vs one rank of pipers. © Public Domain

Article (c) John Crawford 2022

Elizabeth Ford is a flute player, academic and publisher who has been involved with FluteFling for a number of years, performing and speaking at some of our events. Her PhD on the early history of the flute in Scotland was published in book format in 2020 and you can read a review of it in this blog.

Here, Elizabeth describes how she became drawn to early Scottish flute repertoire and to study the history of the flute in Scotland.

My research into the history of the flute in Scotland started informally in 2003, as a Master’s student at the Peabody Conservatory. I was just then learning to play baroque flute and was surprised and somewhat demoralized by how challenging it was. My teacher had assigned a suite by Hotteterre, in a facsimile edition, in the original French violin clef.

I was writing my thesis on Hotteterre’s improvisation manual, L’Art de preluder, so this was good for me. But now and then, I needed something to remind me that I had actually been a pretty good flute player before I took up baroque flute, so I was combing the shelves of the library looking for 18th-century flute music that wasn’t depressingly challenging and that I wasn’t already familiar with. I happened upon Jeremy Barlow’s edition of James Oswald’s Airs for the Seasons. I knew my teacher wouldn’t approve because it was a modern edition, and Scottish; this music was outside the canon and we were not there to challenge the canon. Personally, I think the Peabody Conservatory is exactly the place to do so, but that’s a different topic.

I had always been interested in Scotland, but I didn’t know very much about it as a country or culture. The only recordings of Scottish music I could find at this time were by the Baltimore Consort, which happened to be my favorite band.

I kept my Scottish music tendencies to myself, yet after graduation I started to explore music from Scotland, especially for flute, in greater detail. I kept coming back to Oswald, and how delightful and satisfying his music was to play and to hear. I amassed a large collection of photocopies of music and performed this repertoire any chance I got. I didn’t get into the traditional/art music debate because having been trained in French 18th-century performance practice, I didn’t know what to do with the questions of national identity and ‘traditional’ as it related to music. I had been taught to think that playing by ear was somehow inferior to reading music…even though baroque music is and was largely improvised.

While a law student a few years later, I acquired Concerto Caledonia’s recording Colin’s Kisses: The Music of James Oswald. It was the most exciting, fun recording I’d ever heard. I had a new favorite band and was completely down the rabbit hole. I started reading as much as I could find in the West Virginia University library about Scottish music, and it wasn’t much. David Johnson, Henry Farmer, and that was it. What I kept coming back to was their assertion that the flute was unknown in Scotland prior to 1725. That really bothered me. One thing led to another, and I contacted John Butt and David McGuinness at the University of Glasgow, who said that this would be an excellent PhD topic.

This is the question from which all my research on the flute in Scotland sprang: how, if there was no flute in the country prior to 1725, was there so much flute music published so early in the century? If an instrument wasn’t known or wasn’t popular, it would presumably take a while before composers or music publishers started marketing for it. But, as I made my way through the secondary literature, I realized that this date of 1725 had never before been challenged.

To me, this was ludicrous. The one-keyed flute was developed in France sometime before 1692 (the first image is on the title page of Marin Marais’s Pieces en trio) by a member of the Hotteterre family. The addition of the key revolutionized music: a formerly one-piece non-chromatic instrument with a limited range became fully chromatic, in three pieces, and with wide range. The flute was very popular in France, and considering the long and well-established relationship between Scotland and France, it didn’t make sense to me that no flutes travelled back home with a visiting Scot. I wondered if music scholarship had become victim to that unfortunate ailment, the Scottish Cringe.

These questions guided me I as began my archival research. I quickly found evidence for the flute in Scotland prior to 1725 in the National Record Office. I know that this can sound like I’m saying previous scholars didn’t do their work properly, but that’s not my intention. My predecessors were not focused on the flute, lacked my background in flute history, and didn’t have any reason to question the date. I then began to challenge the historiography of Scottish music scholarship, and its reliance on antiquarian sources.

So, this is the long story of how and why I study the history of the flute in Scotland. My next task is to determine when it disappeared from Scottish music, as until recently most contemporary Scottish traditional flute players would assert that there is no historic evidence for the flute in Scotland and they must look to Ireland for culture, tradition, and repertoire. This is obviously incorrect, but it has been the prevailing assumption, and I want to know why that’s the case.

Here are some factoids on the flute in 18th-century Scotland:

Some of the major composers for flute are William McGibbon, Mr. Munro, James Oswald, John Reid, Daniel Dow, and Francesco Barsanti. Some known flute players include Susanna, Countess of Eglinton, John Reid, Alexander Bruce, the 3rd Duke of Gordon, and Robert Tannahill. Flutes were played in homes, concert halls, and taverns.

Here are some excellent recordings of this repertoire:

Sometime in the 19th century, the flute seems to have disappeared from Scottish music: it stops being mentioned, it stops appearing on title pages, and there are notably fewer flute manuscripts. I’m interested in knowing why and how this happened, and this exploration of historiography and cultural history will (hopefully) be a future project.

Elizabeth Ford won the 2017 National Flute Association Graduate Research Award for her doctoral research on the flute in eighteenth-century Scotland. She was the 2018-2019 Daiches-Manning Memorial Fellow in 18th-century Scottish Studies, IASH, University of Edinburgh. Her complete edition of William McGibbon’s sonatas is published by A-R Editions, and her monograph, The Flute in Scotland from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century, is part of the Studies in the History and Culture of Scotland Series from Peter Lang Press.

In 2021 (hopefully!), Elizabeth will hold the Martha Goldsworthy Arnold Fellowship at the Riemenschneider Bach Institute, the Abi Rosenthal Visiting Fellowship in Music at the Bodleian Libraries, and the American Society for Eighteenth Century Studies-Burney Centre Fellowship at McGill University for research related to James Oswald, Charles Burney, and John Reid. She is co-founder of Blackwater Press.

(c) Elizabeth Ford 2022

November 2021 marked twenty years since Boxwood Aberdeen took place, a weekend that sowed the seeds for FluteFling and inspired many others to further explore the flute in Scottish traditional music contexts.

Organised by Malcolm Reavell for Scottish Culture and Traditions, here he describes the background to the event, which was possibly the largest such gathering in Scotland.

In 1997, representing Scottish Culture & Traditions organisation (SC&T) I contacted Duncan Hendry who was at the time managing the Aberdeen Alternative Festival (now at the Edinburgh Festival Theatre) to see if he would help us arrange to get Alasdair Fraser’s band Skyedance to run a day of workshops for traditional musicians. The lineup at that time was Alasdair on fiddle, Eric Rigler on pipes, Peter Maund on percussion, Paul Machlis on piano, and as American/ Canadian flute player Chris Norman had joined the band, we could have flute a workshop as well.

The workshop was held on a snowy January day in Banchory Academy. Chris Norman had previously held workshops at Celtic Connections in Glasgow, attended by just a couple of people, so when he walked into the room, he was pleasantly surprised to be confronted by about a dozen flute players.

Flute players in Banchory. Chris Norman is front row, in white. Malcolm Reavell to the right of him.

Chris advertised the Boxwood week he ran, and so that was where I went for my holidays the next two years – Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. It was an inspiring event, and I really wanted to do something like this in Scotland, and I got the chance in 2001. Chris got in touch about coming over to Scotland, I jumped at the chance to try and organise something.

I thought it would be good to try out the format Chris used for Boxwood with three tutors covering different styles and traditions. As well as Chris I invited Eddie McGuire whose reputation as composer as well as flute player appealed to classical flute players, and from Limerick, Niall Keegan, who was pushing the boundaries of traditional Irish flute playing.

It was going to cost a bit of money to put on the event. We could not run it for a whole week as Chris did in Lunenburg, but a weekend seemed achievable.

At this time I was still working shifts as an aircraft engineer, so I had days off during the week which I could devote to SC&T (in fact SC&T took up most of my spare time anyway).

I investigated Scottish Arts Council funding and luckily Dave Francis pointed me in the direction of a new funding stream for which few people had applied.

I submitted the grant application and budgeted for about half of the amount I put in the application (that’s kind of normal for such applications). The Scottish Arts Council approved the whole amount. This was not supposed to happen! I had to then revise the programme and remove all the cost saving I had incorporated to use up all the money we were getting (you can’t give it back – you must spend it!).

So… venues for workshops, evening concerts, sessions, accommodation for artists, publicity, leaflets, press releases, flyers, catering,… the machine was set in motion. It wasn’t all plain sailing, I had several weeks, and a few frantic days, sorting out last minute international work permits with the UK Home Office.

Organising it under the SC&T banner gave us access to volunteer resources of the SC&T committee and helpers. The Elphinstone Institute under the auspices of Dr Ian Russell became involved, and Ian gave a talk on the flute bands of NE Scotland. (a photograph of one of the flute bands was used by Chris on his album cover for The Caledonian Flute).

Kenny Hadden helped put out the word to all the flute players we could find in Scotland, and by some magic, we managed to attract participants from the south of England, and one lady (who I had met at Chris’s Boxwood event in Lunenburg) that decided to come all the way from Wisconsin in the US.

The workshops took place in the Aberdeen Foyer. We had an evening concert in Cowdray Hall, and one in the Lemon Tree, and Friday night session in The Globe.

(Left to Right) Chris Norman, Robin Bullock, Niall Keegan, Malcolm Reavell, Dr Ian Russell, Eddie Maguire

The weekend was the first time this number of traditional flute players had gathered in Scotland and acted as inspiration to continue from there. A young Calum Stewart was even in the audience, (although he told me recently, at the time, he didn’t play much flute).

I can’t remember how many participants we had at the weekend, (data protection means I no longer have access to enrolment details), but I seem to have the number 45 in my head.

As for names… well, have fun looking through some of these pictures and try putting names to faces, and a video of the weekend was made by Dr Ian Russell and we hope to make some of it available in the future.

Eddie Maguire and the Whistlebinkies with the participants. Notice the animated music stand. (c) Malcolm Reavell

Aberdeen Press and Journal. Some weel kent faces here: Rebecca Knorr (left) and a young Mhairi Hall centre left, Ann Ward just behind them, a young Calum Stewart (partly hidden behind Mhairi), Munro Gauld and Gordon Turnbull (back right). The lady in the Fairisle pattern sweater is Ann Huntoon from Wisconsin. Apologies for not being able to recall other names at present.

Aberdeen City Evening Express a few days later: Kenny Hadden, Rebecca Knorr and Ann Ward front and centre.

(c) Malcolm Reavell 2021